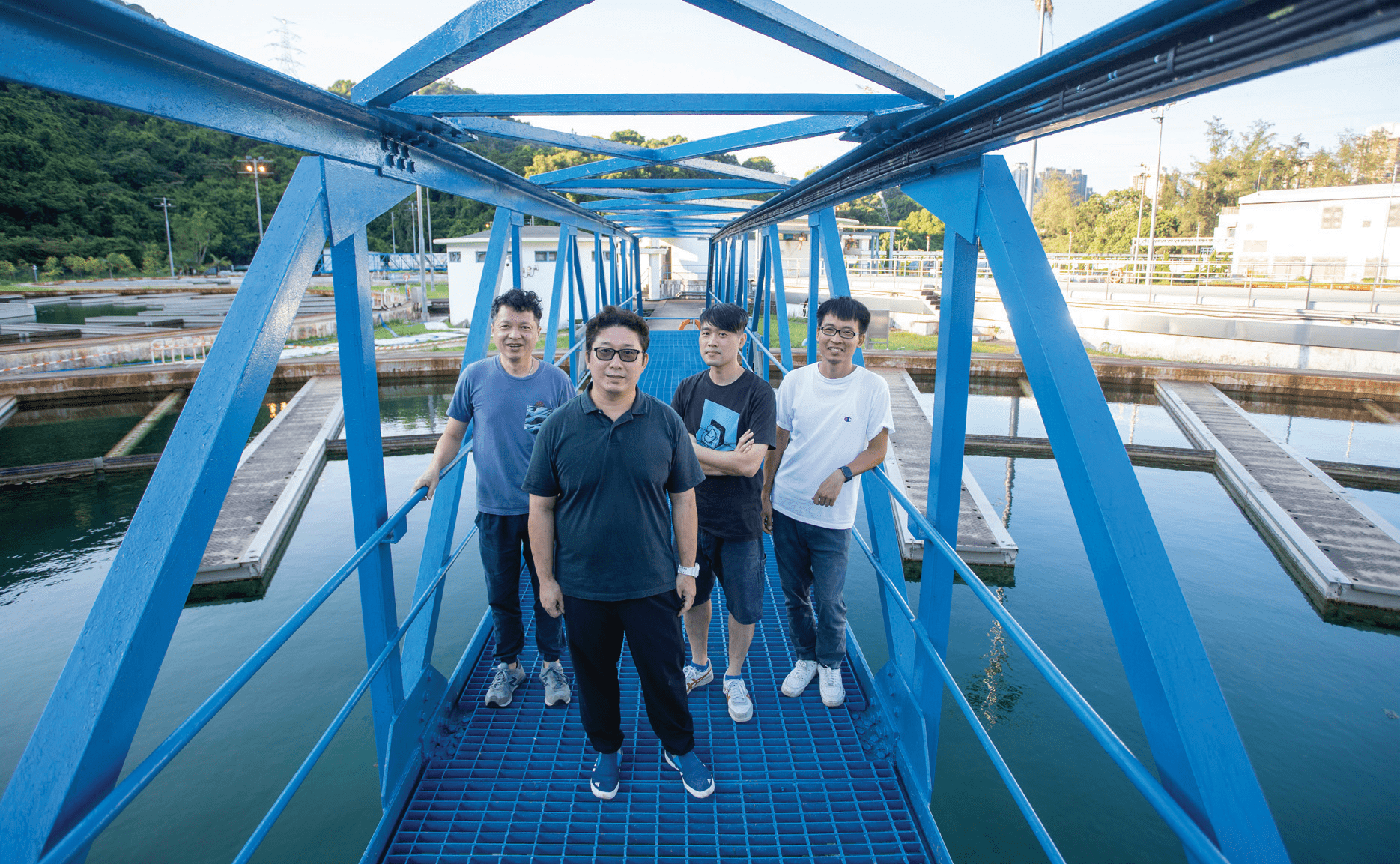

A water treatment works receives raw water, turning it into potable water ready for consumption from the tap. Treated water involves a series of processes and tests, and each stage is interdependent. The Sha Tin Water Treatment Works (STWTW) has the largest daily treatment capacity in Hong Kong and is typical of the city’s treatment facilities whose uninterrupted operation requires many supporting facilities as well as the collaboration of frontline staff. “The personnel responsible for daily operations always respond to the ever-changing situations," says TANG Cho-fung, the STWTW Plant Manager.

The raw water sources for STWTW are more complex than other water treatment works. Apart from receiving Dongjiang water and raw water from reservoirs, the STWTW also receives rainwater during typhoons and heavy storms. This rainwater is collected through rainwater interception tunnels and vertical shafts between Tai Po and Sha Tin. Previously, when water resources were scarce, they had been built to collect as much rainwater as possible. TANG points out that rainwater typically contains sediments; without having time to settle these sediments remain in the raw water making it turbid. The water quality of recently fallen rainwater is normally not satisfactory and requires extra water treatment. Irrespective of the quality of the raw water, the requirements for treated water quality remain unchanged, reiterating the importance of the water treatment process.

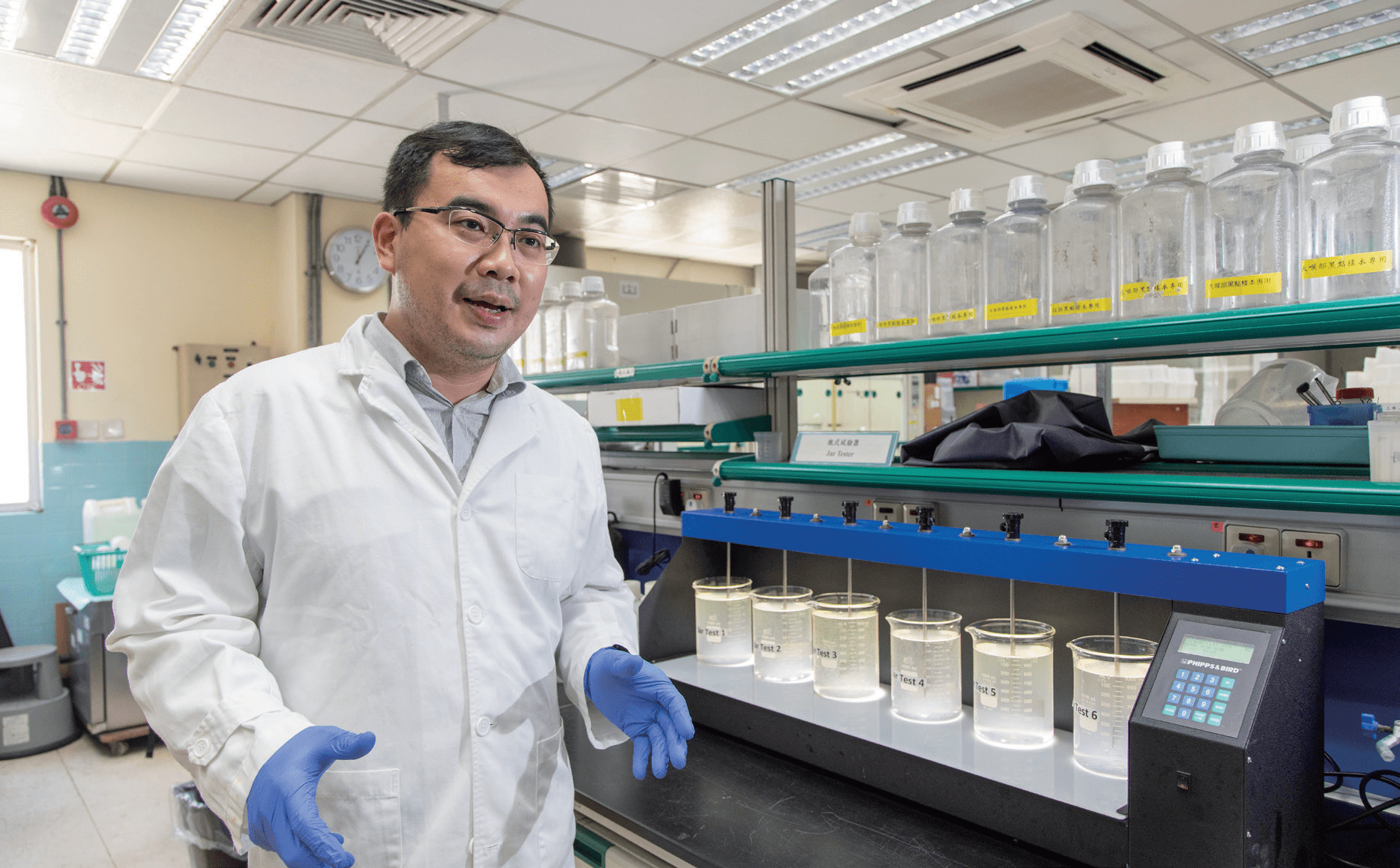

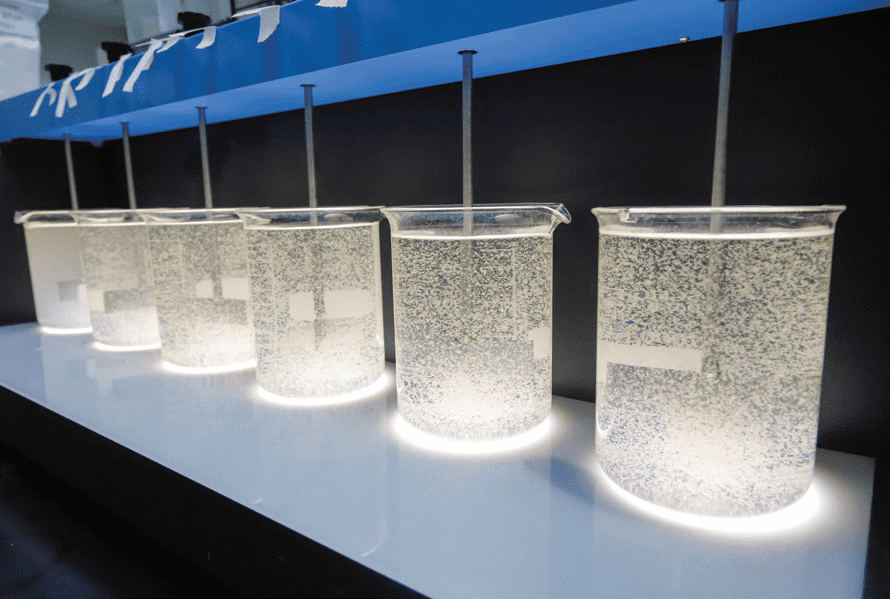

Raw water quality is highly variable in the rainy season, so the operations of the treatment works must be very adaptable to water quality conditions. “Apart from weather forecasting, there is little preparation possible. The quality of the raw water can only be determined through real-time data at the time it is received," explains TANG. In fact, staff at the water treatment works conduct jar tests on every shift. The method involves adding varying amounts of alum to a number of test jars containing raw water samples to determine the optimum flocculation dose. According to Waterworks Chemist CHAN Yuk-chi, if there is an increase in turbidity during rainstorms or a change in the ratio of raw water sources, staff from the laboratory and water treatment works will conduct jar tests more frequently to determine the optimal alum dosage.

Before the current reprovisioning of the STWTW South Works, the STWTW accounted for about a quarter of Hong Kong’s total daily production, supplying water to Sha Tin as well as central Kowloon and Hong Kong Island1. On top of that, STWTW needs to be on-standby to give emergency support. Maintaining continual water output is crucial, placing an immense burden on frontline workers. TANG states that due to the lower electricity tariff at night, STWTW would activate extra pumps between 9p.m. to 9a.m. daily to increase its capacity. This increased activity puts additional strain on equipment and increases the possibility of breakdowns.

Functioning at the heart of STWTW, the water treatment works’ six large pumps transfer treated water from the plant to Kowloon through the Lion Rock Tunnel. A separate electricity substation drives these large motors within the works premises. TANG said that the electricity supply was very stable, but there had been a temporary power outage on one occasion, "The first thing we had to do was to close the gate valve for the intake of raw water. If the raw water had kept coming in while the output of treated water was halted, the system would be in trouble during the emergency repair. The gate valve is operated by electricity, so during the power failure we immediately mobilised six or seven staff to take turns to manually close the gate valve. It took thousands of turns to finally close the gate valve."