Behind every crisis lies an opportunity, but even quality management does not always offer quick solutions. Rather, it involves taking lessons learned from shortcomings and then turning these into opportunities for innovation.

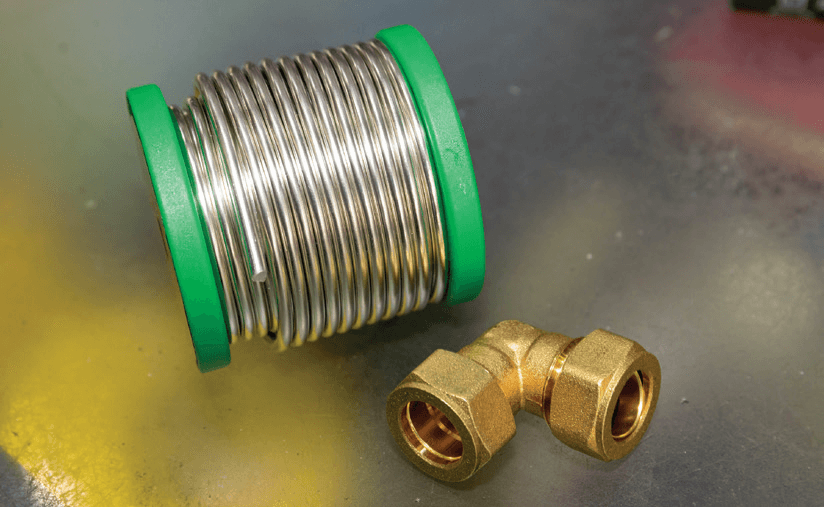

In early July 2015, domestic water samples from Kai Ching Estate in Kowloon were found to contain lead levels higher than the standards set by the World Health Organization (WHO). Subsequently, further cases were found in the same district arousing widespread public concern. Within two weeks, the HKSAR Government set-up an inter-departmental “Task Force on Investigation of Excessive Lead Content in Drinking Water”, and later established a “Commission of Inquiry into Excessive Lead Found in Drinking Water”, with the power to summon witnesses to ascertain the cause of the incident. The inquiry confirmed that the excessive lead content in drinking water was caused by the use of leaded solder in pipe jointing (see the summary table at the end of this article for highlights from the two investigation reports). The Commission then recommended a series of specific measures, including legislation amendments for enhancing regulation and clarification on the roles and responsibilities for the construction, maintenance and safety of the inside service, as well as addressing the potential risks of water contamination of the inside service concerning different types of properties.

The direct cause of the incident was the use of leaded solder in pipe jointing work, a process failure that prompted the government to conduct a holistic review of the city’s drinking water safety regime. In addition to the establishment of the International Expert Panel on Drinking Water Safety in 2016, an expert consultancy was commissioned to develop an "Action Plan for Enhancing Drinking Water Safety in Hong Kong," which was announced in September 2017. The action plan comprises five major areas for improvement, including: a "Drinking Water Standards and Enhanced Water Quality Monitoring Programme", "Plumbing Material Control and Commissioning Requirements of New Plumbing Installations", "Water Safety Plans (WSP)", "Water Safety Regulatory Regime" and "Publicity and Public Education", these are highlighted as follows:

- To establish Hong Kong Drinking Water Standards, with reference to the WHO, the European Union, and seven overseas countries in setting the strategy, rationale and practise for water standards (see the article, “Hong Kong’s Drinking Water Standards” in this chapter for details);

- From December 2017, the WSD has been collecting drinking water samples from the taps of randomly selected consumers throughout Hong Kong and testing the presence of six metals; and from May 2021, additional tests on residual chlorine and Escherichia coli have been conducted (see the article, “The Enhanced Water Quality Monitoring Programme” in this chapter for details).

- Updated the plumbing material standards in the Waterworks Regulations, which took effect from July 2017;

- Launched a Voluntary Labelling Scheme for pre-approved plumbing products in April 2017 to help the public identify products and materials that meet the standards;

- Introduced in July 2017 a systematic flushing procedure for new water pipes as part of a building’s commissioning work to reduce metals leached from new pipes and fittings, with requirements, including six-hour stagnation water sample tests;

- Launched a Surveillance Programme in October 2017 to spot-check plumbing products with valid General Acceptance using a verification test;

- Promulgated the "Technical Requirements for Plumbing Works in Buildings" in August 2018 to provide comprehensive information for the plumbing industry to reference;

- Legislation amendments to define the duties of licensed plumbers, setting out clearly the designated persons for carrying out plumbing works and their responsibilities, which came into force on 15 February 2018;

- Enhancing the knowledge and professionalism of licensed plumbers, including strengthening the syllabi of licensed plumbers’ training courses, implementing a voluntary Continuing Professional Development Scheme and carrying out random inspections by the WSD of new plumbing works under construction.

- In accordance with the recommendations of the WHO, the WSD developed and implemented the departmental WSP in 2007 for use within the department, with a forward-looking perspective on risk management, which was further developed to a Drinking Water Quality Management System in 2017 (see the article "Water Safety and Its Monitoring" in this chapter for details);

- Promote the “Water Safety Plan for Buildings (WSPB)” - under the enhanced “Quality Water Supply Scheme for Buildings - Fresh Water (Management System)” - to property owners and management managers, as recommended by the WHO, and provide incentives to encourage their participation.

- In January 2018, the Development Bureau (DEVB) set-up a Drinking Water Safety Advisory Committee, comprising academics and experts of the related fields, to give advice to the DEVB on various drinking water safety issues.

- A dedicated team was set-up in November 2018 to oversee the performance of the WSD in respect of water safety, including formulating monitoring mechanisms to monitor WSD’s performance on drinking water safety, regularly examine WSD's water quality monitoring data, and conducting auditing and surprise inspections.

- To take forward the above action plan - notably the Enhanced Water Quality Monitoring Programme and WSPB - it is necessary to raise public awareness and gain their endorsement. Therefore, continuing publicity and education are planned using various channels, including a dedicated website, announcements of public interest, teaching materials for students, leaflets, posters and seminars, etc. (refer to Chapter 6 for details of the WSD's publicity and education efforts in recent years).

The above initiatives were all rolled-out in the three years following the lead in drinking water incident. The incident raised the public’s awareness of the responsibilities of property owners and consumers on the maintenance of the inside service. In particular, there is a need for regular cleaning and maintenance after taking possession of a building. The WSD has also stepped-up monitoring and technical support by extending its risk assessment of water safety from "source to connection point” to “the tap" of each building unit. In addition, the WSD also provides continuing support, encouragement and education to the public.

Chaired by then-Deputy Director of Water Supplies, the Task Force on Investigation of Excessive Lead Content in Drinking Water comprised inter-departmental representatives, and three experts and academics. The Task Force completed its investigation three months after its establishment and submitted its final report to the DEVB. The investigation involved dismantling over 100 pipes and fixtures from the Kai Ching Estate and Kwai Luen Estate, and conducting leaching tests, elemental analyses of various components, lead isotopic analysis and mathematical modelling. It also compared these results with the water supply chain of a reference housing estate using stainless steel pipes without soldering. At the same time, nine other water samples were examined, all of which were from the inside service of the housing estates that had excessive lead content. The pipes used were similar in the design and installation specifications to those in buildings in the lead incident. Upon comparing the three sets of data and information with each other, it was found that the test results for the water samples without soldered pipes did not exceed the standard. Whereas, the pipes of the other two sets of water samples with excessive lead were all soldered.

The Task Force is of the view that the incident reflected a lack of awareness among stakeholders in the construction industry of the use of leaded soldering materials and its detrimental effects on the quality of drinking water. To avoid similar incidents in the future, the Task Force recommended a series of measures to prevent the use of leaded solder materials, and non-conforming pipe fittings. The report also recommends the WSD to investigate alternative piping materials.

The government established and appointed the Commission of Inquiry into Excess Lead Found in Drinking Water to ascertain the causes of the incident and to review and evaluate the regulatory and monitoring system in respect of drinking water in Hong Kong. The Commission was chaired by then-Judge of the Court of First Instance of the High Court, Mr. Justice Andrew CHAN Hing-wai, who also served as a member of the Commission. Another member appointed was former Ombudsman, Alan LAI Nin. The Committee then appointed three expert witnesses to assist it in the hearings.

The Committee held hearings for a total of 67 days, summoning 72 witnesses to give evidence. The report was completed after a seven-month investigation, and found that there were no statutory provisions to clearly define the quality of water at the water tap and who should bear the respective responsibility; this resulted in regulatory and monitoring deficiencies.

Hong Kong had banned leaded water pipes in buildings as early as 1938. The use of leaded solder in plumbing works was prohibited in 1987. However, there was still a lack of standard values for lead content in potable tap water, nor were there any clear indicators for the community to follow.

Finally, the Commission recommended a series of improvement measures that the WSD has subsequently implemented, leading to a revamp of the city’s entire water safety strategy.