Ancient Rome’s 2,000-year-old water supply system is one of the world's great architectural wonders. Did human civilization enable the construction of such great water supply systems, or vice versa? Although Hong Kong’s first public waterworks projects were hampered by financial constraints, the construction of the city’s second reservoir, the Tai Tam Reservoir1, benefited from a variety of favourable factors. Significantly, Hong Kong's urban development began at the height of the European industrial revolution and this project was at the forefront of international engineering technology. Similarly, the city’s future large-scale waterworks projects gained from subsequent engineering and technological developments. Despite Hong Kong's fast-paced urban development, many of the city’s original waterworks facilities have stood the test of time and are still in excellent operational use today.

Ir CHAN Tze-ho explained that, "Since we work in the WSD, we know the waterworks and systems very well and greatly admire the heritage buildings and structures. We see not only the grandeur of their design, but also the origins of the entire water supply system. There is always a reason for designing a project in such a way. This is what makes it so informative for us when looking back over the history of the waterworks’ monuments and the history of the projects when researching the traces and drawings left behind.”

Former Chief Engineer Ir CHAN Tze-ho and current Senior Engineer Ir WONG Hei-nok of the WSD cover two generations of expertise overseeing the waterworks’ historical facilities and monuments. Both engineers have been involved in a number of studies to facilitate the historical grading of waterworks facilities since 2000. During their research they learned more about the waterworks history and have become increasingly motivated to share their experience and knowledge in their day-to-day maintenance work.

The 42 Waterworks Monuments

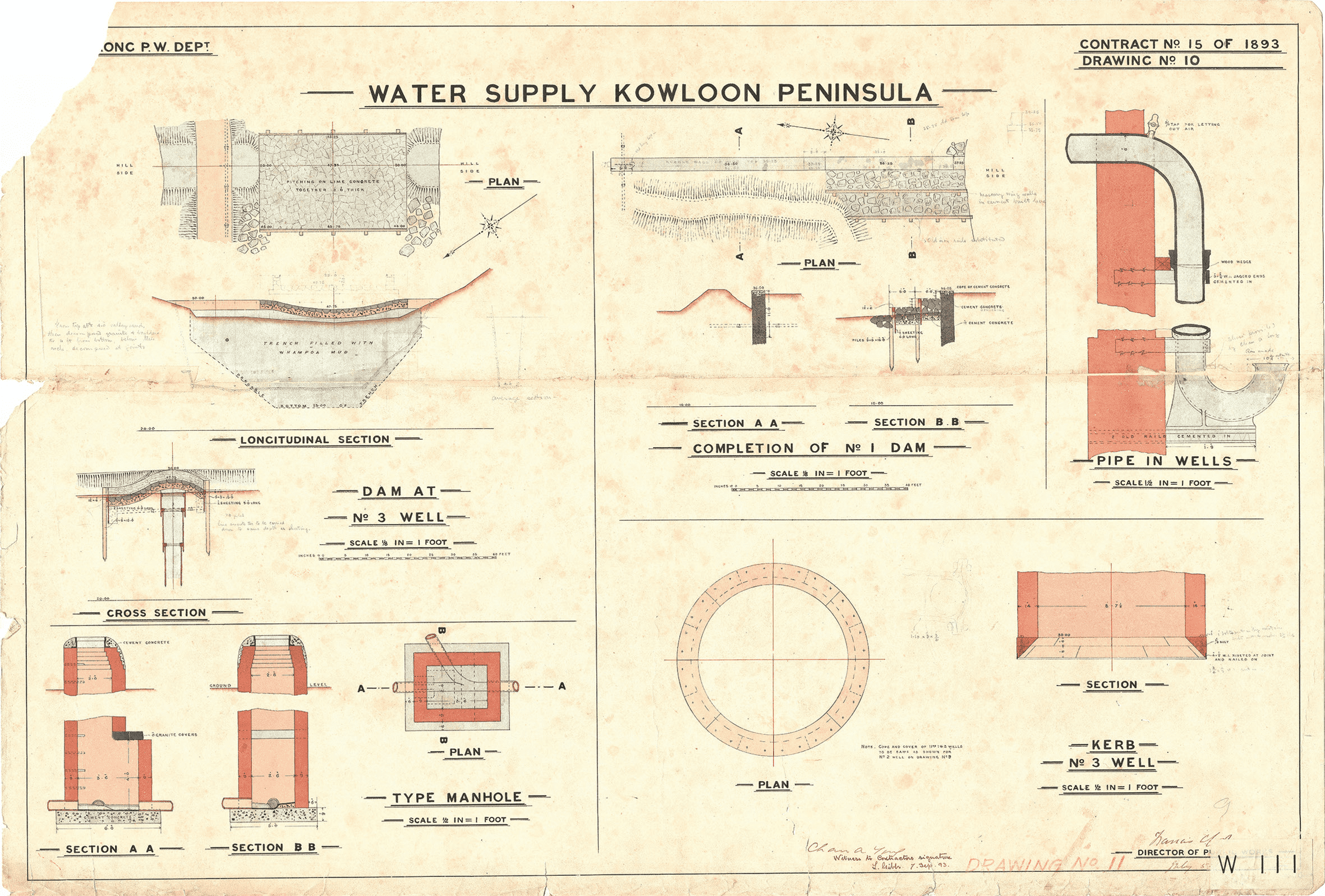

Ir CHAN remembers that when he was posted to the WSD Design Division over 20 years ago, he frequently went to the Drawing Office to look for historic drawings prepared by his predecessors. “Back then, digitalization was not widespread and finding information was not so easy. Notwithstanding, it was fascinating to have access to handwritten drafts from a century ago, as they portrayed a vivid picture of the city’s water supply history,” he recalls. He later joined WSD’s editorial team publishing a special publication commemorating 150 years of water supply in Hong Kong. This allowed him to further explore the history of Hong Kong’s waterworks. In 2009, Mrs Carrie LAM CHENG Yuet-ngor the then Secretary for Development and the Antiquities Authority, requested the WSD to explore conserving historic waterworks facilities. At that time, Ir CHAN became the principal researcher in preparation for the heritage assessment and grading of the waterworks facilities. During this assessment, the WSD provided information on 41 waterworks structures to the Antiquities and Monuments Office and the Antiquities Advisory Board.

As of June 2022, there are 132 declared monuments in Hong Kong. Seven of these are declared waterworks monuments, including 42 historic structures across six reservoir systems and 46 historic buildings rated Grades 1 to 3. The waterworks monuments represent the largest coherent grouping of heritage structures amongst all the declared monuments and historic buildings in Hong Kong. Together with the country parks in which they are situated, they constitute an exemplary component of Hong Kong's cultural landscape. The WSD’s heritage is widely recognised by the general public for its unique combination of natural environment reflecting the history of urban development and the ingenuity of artificial engineering structures. This array of heritage reservoirs declared as monuments were all built before World War II and include: Pok Fu Lam Reservoir, the Tai Tam Group of Reservoirs, Wong Nai Chung Reservoir, Aberdeen Reservoir, Kowloon Reservoir and Shing Mun Reservoir.

These declared monuments of historic reservoir systems comprise 13 masonry bridges or aqueducts with bridging facilities, involving large spanning structures mostly built of granite, reflecting Hong Kong’s geological composition. Whilst the overall design is mostly functional and utilitarian, the masonry walls, columns and arched structures, in particular, demonstrate a subtle influence of the popular neoclassical architectural style prevalent in the late 19th and early 20th century. Adding to their timeless elegance, these reservoirs are surrounded by forests of tall shady trees, often situated far from other urban buildings and occupying vast green areas with unobstructed views.

The Tai Tam Group of Reservoirs with 21 historic structures accounts for half of the total number of declared waterworks monuments, making this reservoir possess the highest number of declared heritage buildings. In total, they form a five-kilometre long heritage trail that is a two-hour walk around Tai Tam Upper Reservoir, Tai Tam Byewash Reservoir, Tai Tam Intermediate Reservoir and Tai Tam Tuk Reservoir. The Tai Tam Reservoir project set a precedent in public financing for infrastructure at the time, as the scale of the original project was increased to over HK$1 million. The project also pioneered the use of a drilling rig to build Hong Kong's first water transfer tunnel. The project also introduced a local concrete engineering method that enabled the construction of the largest concrete dam in the British colonies at that time. This project greatly contributed to the increased local production of cement, and changed the city’s established construction methods over the following years2.

Five Key Features of Waterworks Heritage

After years of research, Ir CHAN identified that, “There are five key features of waterworks heritage structures. They need to be: ‘site-specific’, ‘use local materials’, have a ‘mixture of aesthetics and function’, have ‘good documentation’, as well as being ‘bold and innovative’.”

"Site-specific" refers to the design of reservoirs or related facilities to suit the geographical surroundings. For example, the Kowloon Reservoir system was built after the lease of the New Territories was granted to cater for the scarcity of fresh water on Hong Kong Island and in Kowloon. Despite being named the Kowloon Group of Reservoirs, they are actually located in the New Territories. The four reservoirs were built according to the topography of the hills, making good use of gravitational flow. Two water treatment works, Shek Lei Pui Water Treatment Works (SLPWTW) and Tai Po Road Water Treatment Works (TPRWTW), are located not far away, forming a clear and visible water supply network.

Practical considerations during the design of each project govern the use of the most suitable materials. This means using different components to construct a facility. The Ex-Sham Shui Po Service Reservoir at Mission Hill is a rare example of a service reservoir that combines a variety of materials, using granite, red bricks and concrete. Ir CHAN explains that the architecture is dependent on its specific use of material, “Inside the interior of the reservoir, stone has been used for columns because they have a greater load-bearing capacity. Red bricks are used to create curved arches, while concrete is used for large spans. In many cases, raw materials, particularly granite, were sourced on-site at the waterworks.”

Waterworks heritage structures are often aesthetically and functionally pleasing. The methods and styles of construction used show their popularity at the time and the great thought that went into their design. According to Ir CHAN, “Early waterworks projects were bold and innovative, employing the most up-to-date and cutting-edge technologies. For instance, rapid gravity filtration was adopted at the SLPWTW despite there being only two comparable facilities in the United Kingdom before its introduction in Hong Kong.” The idea of creating reservoirs in the sea, another example, was a world first at the time.

Exploring the Past Through Research

Many of the city’s waterworks facilities are still in use today, which is good news for heritage conservationists and history enthusiasts. Their preservation are assisted with the many original drawings that have been preserved intact due to the facilities’ need for continuing maintenance. This is not necessarily the case for other historic structures, especially those built before World War II, as much documentation was lost during the war. Ir CHAN and Ir WONG have established a history research group with like-minded colleagues to search for missing water supply heritage structures which they research and look for in their free time.

"We usually learn about an old project’s design from documents and drawings”, explains Ir WONG, “Then we set out to plan the route and estimate the approximate location of the missing structure. When we arrive at the site, we observe the terrain and search for possible alignments along the water supply system. We are like detectives.” After examining old drawings, Ir WONG recalled their experience of searching for the original bridge no. 26 that was missing along the Pok Fu Lam Conduit. “The site conditions did not match the location stated in drawings, so by understanding the engineering design, we reckoned that the alignment had probably been altered during construction. We eventually discovered the old bridge hidden in grass at a lower level. We were thrilled!”

Historic Waterworks Facilities Still Serving the Public

“When we investigate historic structures, we often find that old buildings have been significantly altered for practical reasons,” Ir CHAN explains. “For example, the roof of the decommissioned valve house at Wong Nai Chung Reservoir was originally designed with a pitched Chinese-tiled roof, but because of water leakage, the maintenance staff quickly replaced it with a flat concrete roof.” This modification understandably solved the urgent problem of water leakage at the expense of aesthetic considerations.

Ir WONG, who is currently responsible for reservoir safety, says the WSD regularly maintained facilities. “Heritage conservation standards now ensure that maintenance work on our 42 monuments listed waterworks facilities are undertaken properly.”

Our Heritage for Future Generations

Before retirement, Ir CHAN had been in charge of the maintenance of the Ma On Shan Water Treatment Works. He recalled discovering in 2014 an endangered and precious incense tree on the hillside, close to the Works’ boundary fence. “The tree was in poor condition and hence special arrangements were made to transplant it to a better location. The daily works and decisions made by team are of crucial to preserve our heritage for future generations.”

In a similar vein, Ir WONG added that drawings are crucial documents that give evidence of the historical value of heritage structures and buildings. “The WSD liaises with the Government Records Service to restore, classify and archive old drawings and documents. Hopefully, in the future, an online exhibition will be launched to make these valuable historical materials more accessible to the public.”

- The Tai Tam reservoirs, which includes the Tai Tam Upper Reservoir, Tai Tam Byewash Reservoir, Tai Tam Intermediate Reservoir and Tai Tam Tuk Reservoir, was constructed in phases between 1888 and 1917.

- Ma Guangyao. (2011). The Story of the Opening of Tai Tam Reservoir - A Turning Point in the History of Engineering in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing (Hong Kong) Ltd. 169 - 202.