Hong Kong has little flat land and a predominantly hilly coastline topography with many surface streams, but no large rivers or lakes. Its geology is mostly volcanic and granitic, which is not conducive to storing large amounts of groundwater. In its early years, Hong Kong needed to exploit and collect water sources to meet the water needs of the growing population. In 1859, the government offered a £1,000 reward for proposals, and S.B. RAWLING, Clerk of Works in the British Royal Engineering Department, proposed the construction of a reservoir in the Pokfulam valley, which was accepted. The government then sought the private sector to invest in the development of water supply services, but unlike other utility services such as electricity, gas and ferry routes, waterworks projects were an unattractive investment because of the large capital costs and uncertain long term returns. The government decided to publicly fund the development of the city’s massive network of water reservoirs over the last century. From these earliest beginnings, the WSD is now one of the few public sector in the world responsible for the city’s water supply systems.

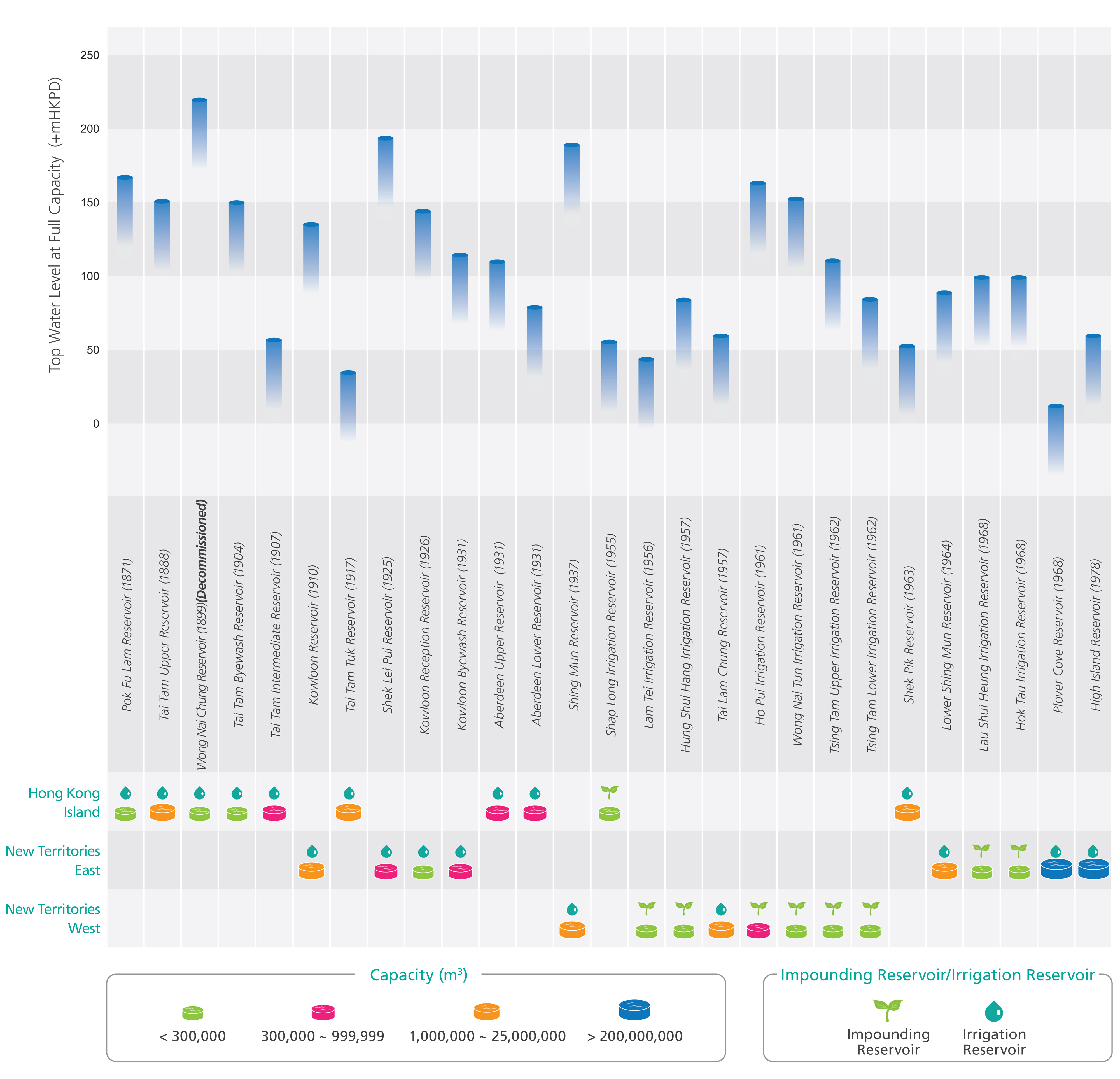

- *mcm = million cubic metres

Highlights of Hong Kong's Impounding Reservoirs

Completed in 18631, Pok Fu Lam Reservoir is the oldest of the 17 existing water supply impounding reservoirs in Hong Kong. The highest is Shek Lei Pui Reservoir (completed in 1925) with the top water level of 195.1 metres above Hong Kong Principal Datum (+mHKPD), an equivalent height as Mount Johnston, located on the southern side of Hong Kong Island. Previously, Wong Nai Chung Reservoir (completed in 1899) was higher, with the top water level of +220.98mHKPD, but its importance diminished as bigger water supply facilities came on stream; in 1986 it was converted into a park with boating facilities. The largest impounding reservoir, the High Island Reservoir (completed in 1978), has a capacity of 281 million cubic metres (mcm), accounting for nearly half of Hong Kong’s current total impounding reservoir capacity and more than 1,200 times the capacity of Pok Fu Lam Reservoir, the city’s first reservoir. Hong Kong’s population of 124,000 in 1863 has since grown dozens of times over the last one hundred years.

Top Water Level of Reservoirs by Region Over the Years

Altitude of Reservoir Sites and Their Development

| Name of Reservoir | Year of Completion | Capacity (m³) | Top Water Level at Full Capacity (+mHKPD) | Impounding Reservoir/Irrigation Reservoir | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pok Fu Lam Reservoir | 1871 | 233,000 | 168.52 | Impounding Reservoir | Hong Kong Island |

| Tai Tam Upper Reservoir | 1888 | 1,490,000 | 152.31 | Impounding Reservoir | Hong Kong Island |

| Wong Nai Chung Reservoir | 1899 | 109,000 | 220.98 | Decommissioned | Hong Kong Island |

| Tai Tam Byewash Reservoir | 1904 | 80,000 | 151.40 | Impounding Reservoir | Hong Kong Island |

| Tai Tam Intermediate Reservoir | 1907 | 686,000 | 58.17 | Impounding Reservoir | Hong Kong Island |

| Kowloon Reservoir | 1910 | 1,578,000 | 136.55 | Impounding Reservoir | New Territories East |

| Tai Tam Tuk Reservoir | 1917 | 6,047,000 | 35.95 | Impounding Reservoir | Hong Kong Island |

| Shek Lei Pui Reservoir | 1925 | 374,000 | 195.10 | Impounding Reservoir | New Territories East |

| Kowloon Reception Reservoir | 1926 | 121,000 | 145.54 | Impounding Reservoir | New Territories East |

| Kowloon Byewash Reservoir | 1931 | 800,000 | 115.80 | Impounding Reservoir | New Territories East |

| Aberdeen Upper Reservoir | 1931 | 773,000 | 111.25 | Impounding Reservoir | Hong Kong Island |

| Aberdeen Lower Reservoir | 1931 | 486,000 | 80.32 | Impounding Reservoir | Hong Kong Island |

| Shing Mun Reservoir | 1937 | 13,279,000 | 190.50 | Impounding Reservoir | New Territories West |

| Shap Long Irrigation Reservoir | 1955 | 133,000 | 56.83 | Irrigation Reservoir | Outlying Islands |

| Lam Tei Irrigation Reservoir | 1956 | 115,000 | 45.11 | Irrigation Reservoir | New Territories West |

| Hung Shui Hang Irrigation Reservoir | 1957 | 91,000 | 85.34 | Irrigation Reservoir | New Territories West |

| Tai Lam Chung Reservoir | 1957 | 20,490,000 | 60.96 | Impounding Reservoir | New Territories West |

| Ho Pui Irrigation Reservoir | 1961 | 505,000 | 164.59 | Irrigation Reservoir | New Territories West |

| Wong Nai Tun Irrigation Reservoir | 1961 | 160,500 | 153.92 | Irrigation Reservoir | New Territories West |

| Tsing Tam Upper Irrigation Reservoir | 1962 | 100,000 | 111.87 | Irrigation Reservoir | New Territories West |

| Tsing Tam Lower Irrigation Reservoir | 1962 | 57,000 | 85.75 | Irrigation Reservoir | New Territories West |

| Shek Pik Reservoir | 1963 | 24,461,000 | 54.03 | Impounding Reservoir | Outlying Islands |

| Lower Shing Mun Reservoir | 1964 | 4,299,000 | 90.22 | Impounding Reservoir | New Territories East |

| Lau Shui Heung Irrigation Reservoir | 1968 | 170,000 | 100.58 | Irrigation Reservoir | New Territories East |

| Hok Tau Irrigation Reservoir | 1968 | 180,000 | 100.58 | Irrigation Reservoir | New Territories East |

| Plover Cove Reservoir | 1968 | 229,729,000 | 13.41 | Impounding Reservoir | New Territories East |

| High Island Reservoir | 1978 | 281,124,000 | 60.96 | Impounding Reservoir | New Territories East |

The most common engineering principle applied in the operation of waterworks is that water flows with gravity. So, from the city's earliest days, the choice of appropriate reservoir sites has adopted this criteria. It aptly follows the Chinese saying that, "Man seeks his way up; water flows down".

Pok Fu Lam Reservoir, Hong Kong’s first reservoir applied this principle. Its deliberately selected location was in an upland valley between High West and Mount Kellett on Hong Kong Island’s western side. This location was a reasonable distance for water conveyance and did not affect the residential and economic activities of the city of Victoria. As seen from the graph “Top Water Level of Reservoirs by Region Over the Years”, the highest reservoirs were of a relatively small capacity and built before World War II. Due to population growth and the rapid development of urban areas across Hong Kong, subsequent reservoirs were constructed in larger scale and at locations covered from Hong Kong Island to the New Territories.

It is difficult to have large land areas found for impounding reservoirs due to the scarcity of suitable upland valleys or steep canyons. Alternatively, small-scale reservoirs hardly meet the water needs of a growing population.

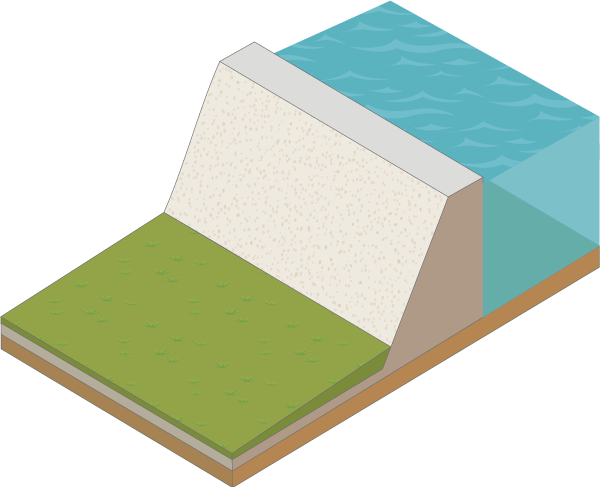

Hong Kong’s most recently built impounding reservoirs were built on low-lying land along the coastline. Plover Cove Reservoir (completed in 1968) was built directly in the sea, with seawater being drained and replaced with fresh water. Plover Cove was previously a bay surrounded on three sides by mountains, a main dam was built to create the inner lake as a large water storage area. This was lauded as an engineering breakthrough around the world at the time. A similar construction technique laid the foundations for the much larger High Island Reservoir (completed in 1978). These two waterworks projects increased the total capacity of Hong Kong's impounding reservoirs from about 75.2 mcm to 586 mcm, almost an eightfold increase in 15 years; reflecting Hong Kong's rapid economic and population growth after World War II.

Irrigation Reservoirs

In addition to constructing water supply impounding reservoirs, nine irrigation reservoirs were built in Hong Kong during the 1950s and 1960s. These reservoirs (see those marked with a green leaf in “Top Water Level of Reservoirs by Region Over the Years”) were built to compensate local farmers for diverting water sources from nearby farmland during the construction of the city’s four largest waterworks projects, Shek Pik Reservoir, Tai Lam Chung Reservoir, Plover Cove Reservoir and High Island Reservoir. Today, these irrigation reservoirs are integrated into the countryside, making the mountains and water beautifully complement each other.

To store water you need a holding vessel. For a person, this could be a 'cup'; for a building, it could be a ‘tank'; for a city, it could be a 'pool', a 'lake' or a 'reservoir'. Although differing in size, they all serve as enclosed storage spaces. The deeper and wider they are, the greater their capacity. However, the more water is stored, the greater the weight and corresponding gravity, as well as the impact on the surrounding environment. The construction of impounding reservoirs is a science of mechanics requiring precise calculations.

Impounding reservoirs built in valleys must be surrounded by mountains with dams built as barriers at the gaps, regardless of their elevations. The engineering structure of a dam needs to be designed according to the topography and scale of the site. Hong Kong’s impounding reservoirs use two main types of dams: a gravity dam (mainly built with concrete) and an embankment dam (mainly built with earth materials or rocks).

Tai Tam Tuk Reservoir and Shing Mun Reservoir, completed in 1917 and 1937 respectively, both adopted a gravity dam design for their main dams. These two challenging projects increased Hong Kong's overall water storage capacity by two-fold. At the time, Tai Tam Tuk Reservoir was described as "Asia’s Number One Dam", surpassing even similar projects in the United Kingdom and its then-dependencies.

Situated in an upland gorge, the Shing Mun Reservoir was designed with the top water level of +190mHKPD at its full capacity. It was a large infrastructure project responding to Hong Kong Island and Kowloon’s rapid increase in population at the time. As a result of the need to increase the reservoir's storage capacity, the main dam was repeatedly raised to eventually reach a height of 85 metres. Concrete is usually chosen for building gravity dams; however, it is a costly material. Since there was an abundant supply of granite in the vicinity, granite instead of concrete was utilised to create a rockfill. In addition, a pipeline constructed across Victoria Harbour transferred fresh water from the middle of the territory to Hong Kong Island. Nearly 2,500 engineers and workers were hired to work on the entire project which was acknowledged at the time as a significant and groundbreaking feat of engineering.

Before the 1970s, Hong Kong experienced such rapid population growth that there was always a shortage of water. It was common to plan for the construction of the next reservoir before finishing the current project, leading to a continuous string of impressive waterworks projects during this period.

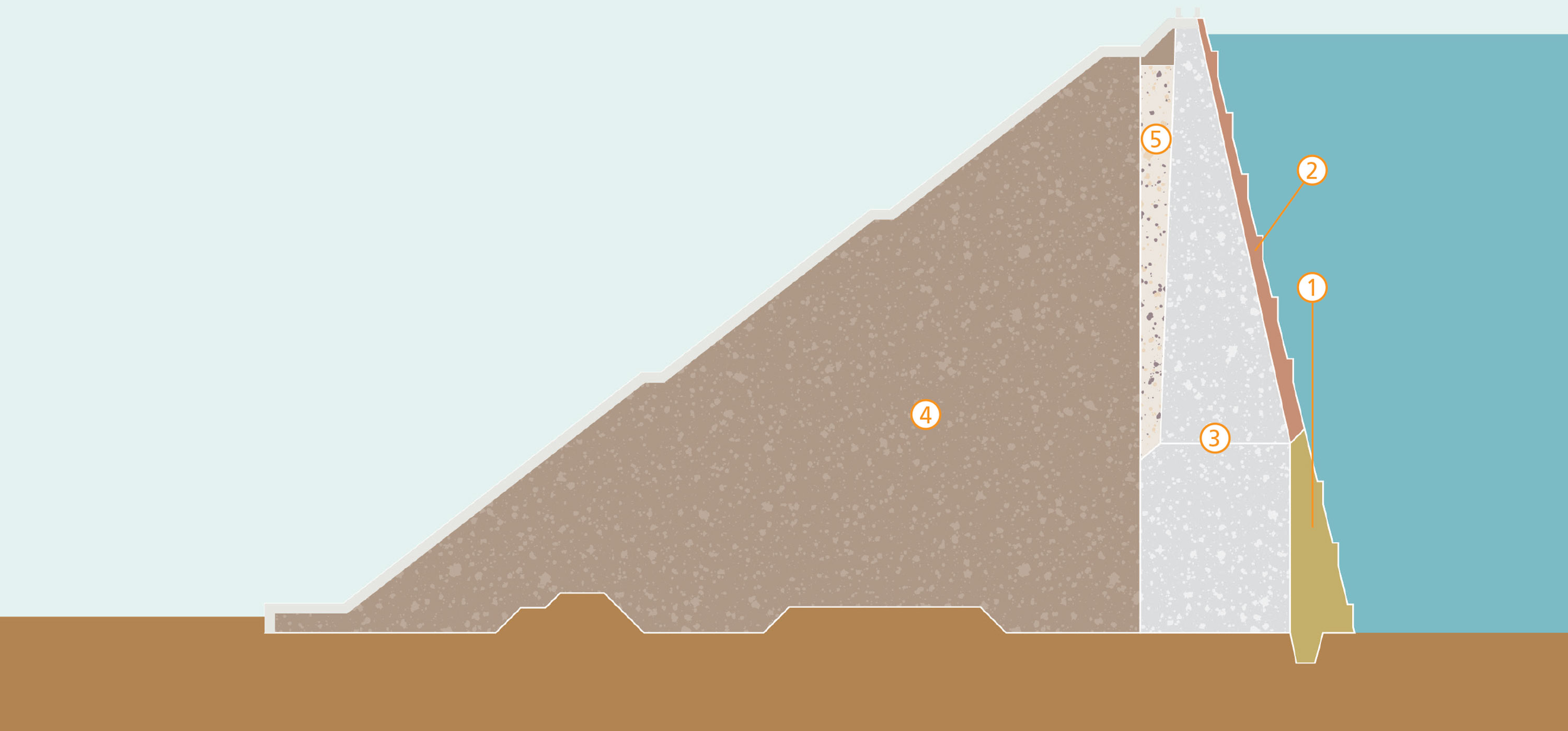

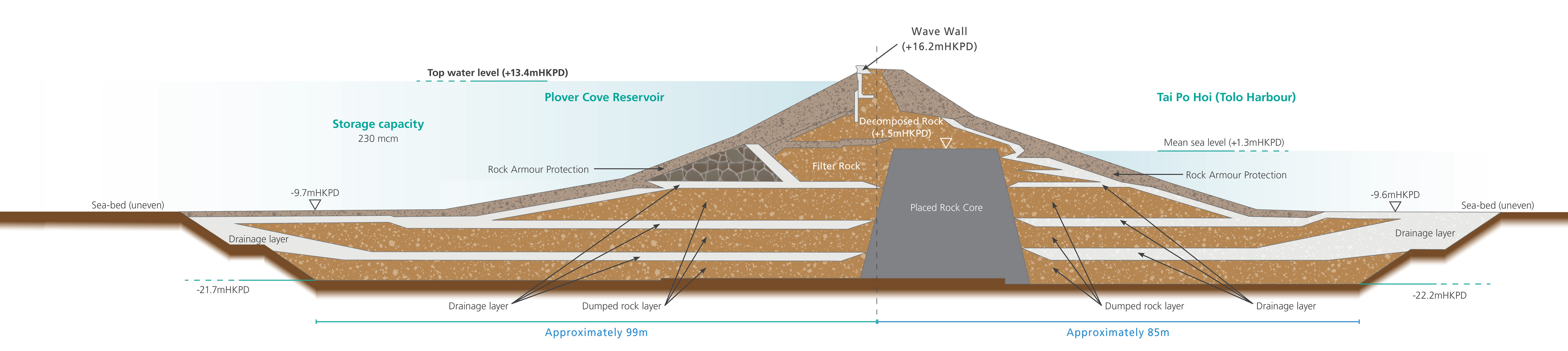

Plover Cove Reservoir, conceived in the late 1950s and completed in 1968, was the first reservoir in the world to be built in the sea. Although the site was surrounded by hills on three sides, it required the construction of a two-kilometre-long main dam (plus three shorter subsidiary dams) to create an inner lake that could withstand the pressure of water stored 12 to 13 metres above the average sea level. The dam is twice as long as the distance across Victoria Harbour between the Tsim Sha Tsui and Central ‘Star’ Ferry piers. To this day, it remains Hong Kong’s longest reservoir dam. Its underlying method of construction is also one of the most ancient and commonly used designs in the world. The dam’s materials were mainly sand and gravel, piled-up in layers. Although it is a basic engineering principle, it was a magnificent achievement building a ‘tower’ from sand and forming a dam from stones in the sea.

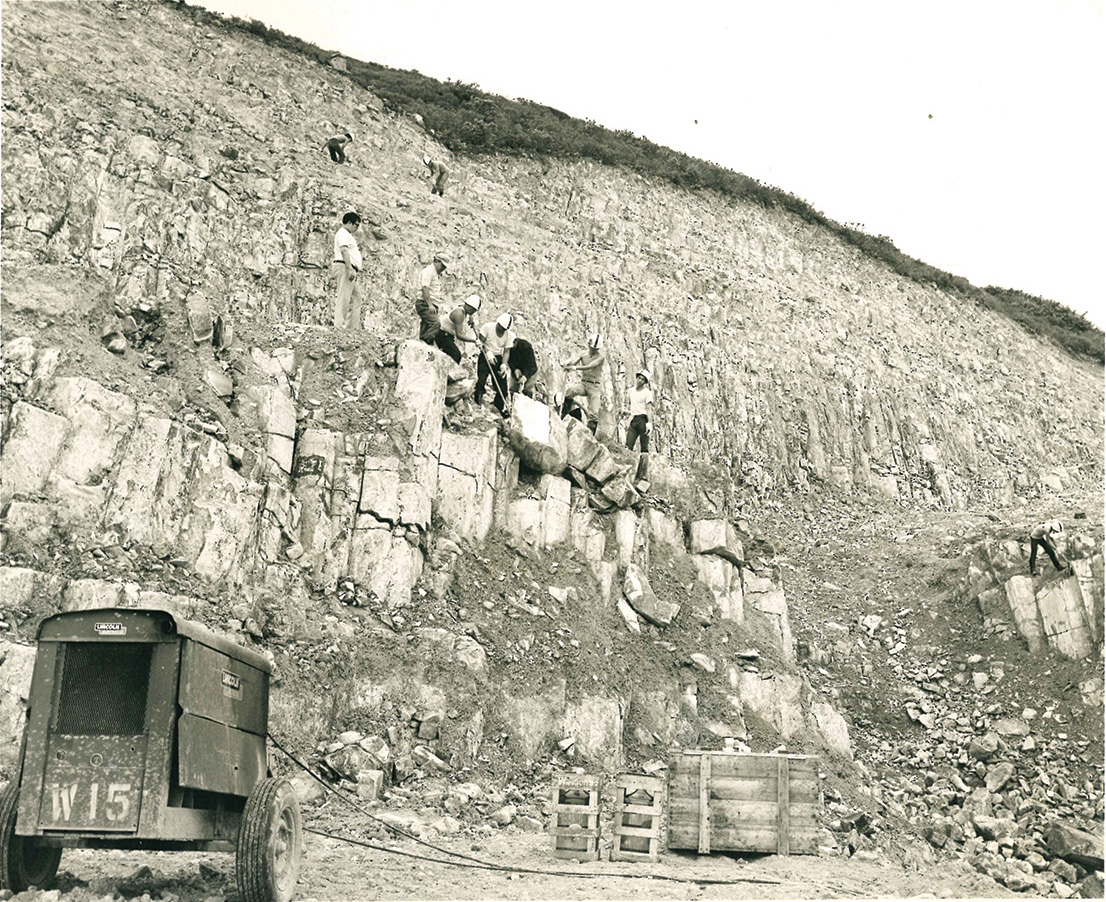

The construction of Plover Cove Reservoir was divided into three stages. The first stage involved the construction of the Sha Tin Water Treatment Works, the associated water tunnels and intake system. The second stage involved the construction of the dam. It was built from materials quarried from Ma Liu Shui, now The Chinese University of Hong Kong and at Turret Hill Quarry in Ma On Shan. The dam was built by digging a deep trench over 207 metres wide to lay the foundations (see “Section of Plover Cove Reservoir main dam”). This was followed by an alternating layer of gravel and sand, the weight of which was used to reinforce the core foundation. The upstream and downstream faces of the dam are protected by rock armour. Technical instruments were located inside the dam to monitor the condition of the structure. After the completion of the subsidiary dams, it took about four months to drain the seawater out of the enclosure, followed by another four months to fill with raw water before the water supply system could be put into operation. At the final stage in 1970, the government decided to increase the height of the dam. It was completed three years later and raised the water storage capacity by nearly 35% to 230 mcm.

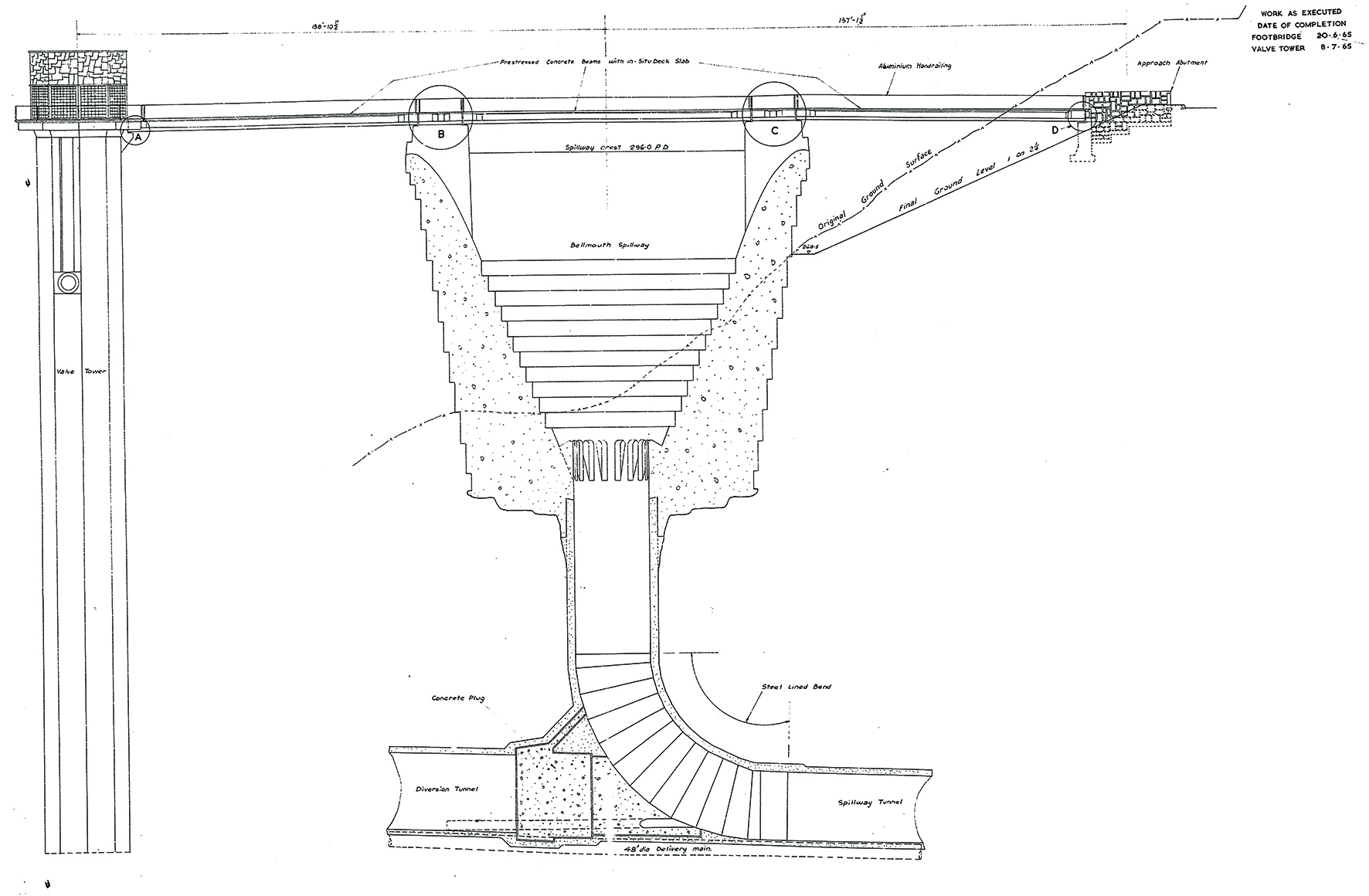

As a territory-wide water storage system, the basic function of a reservoir is to store water. It is also designed to drain and transfer the excessive inflow when the reservoir is overloaded. A spillway is designed to allow excessive water to be released away from the reservoir in a controlled manner. It prevents high water levels in the reservoir from endangering facilities or access roads on a dam crest, and prevents overtopping that washes the downstream dam face not designed to run water. In some cases, a road is placed above the spillway for pedestrian or vehicular traffic.

The large circular hollow structure, known as a 'bellmouth spillway', in the reservoir and connected to an underground drainage tunnel, is often a popular photographic attraction for the public. It drains excess water to a downstream area. For example, the Upper and Lower Shing Mun Reservoirs each have a bellmouth overflow with a height equivalent to the top water level. When the Upper Shing Mun Reservoir is full, the water will flow down to the Lower Shing Mun reservoir via the bellmouth spillway. When the Lower Shing Mun Reservoir is full, the water will then overflow through the spillway to the Shing Mun River at lower level and then out to Tolo Harbour.

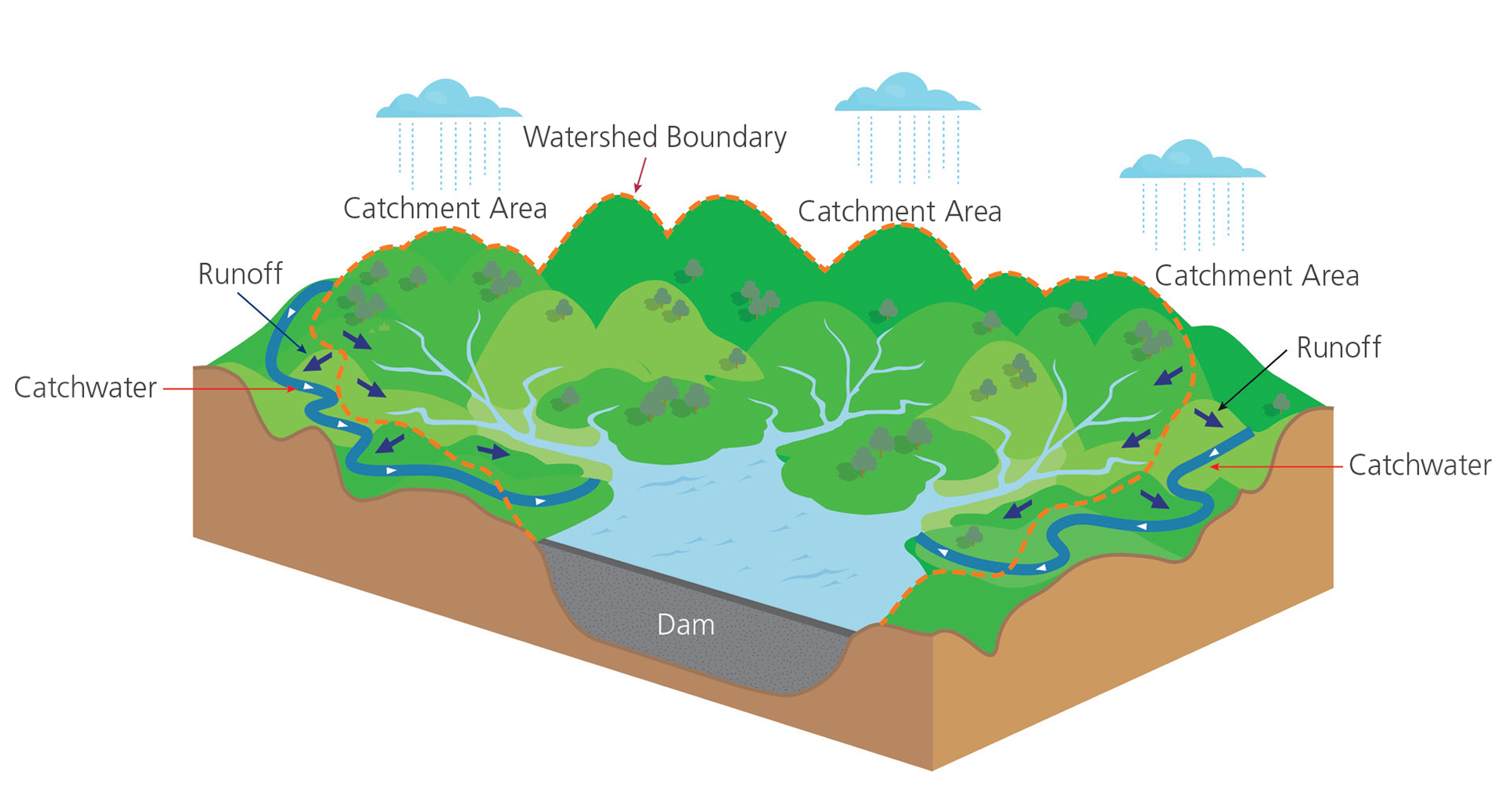

Gathering Grounds and Catchwaters

Reservoirs are built in gorges and valleys surrounded by mountains. A reservoir’s catchment area is formed from the highest points of these mountain ridgelines. Meanwhile, some rainwater falls directly into the reservoirs and some flows via natural streams and rivers. In the absence of human intervention, there is a high chance of water loss as rainwater falls on the slopes or streams on the other side of the watershed, eventually ending up in urban storm drains or the sea. To collect rainwater more efficiently, the WSD also builds catchwaters on the opposite side of the watershed to redirect untreated water to reservoirs or water collection sites that would be otherwise lost.

In 1898, the British and Chinese sides signed the Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory to further lease the New Territories. It led to the government's plan to build the Kowloon Reservoir in 1901. In 1902, 32 boundary stones were erected on the ridge line of the valley to the west of Beacon Hill and south of Needle Hill to mark the extent of the natural catchment area, to improve the collection of rainwater. Messrs Denison, Ram & Gibbs, the Hong Kong architectural and engineering consultants, recommended adding a catchwater system. In March 1904, $40,000 was successfully sought from the Legislative Council for the project.

There are currently 45 catchwater systems, with a total length of 120 kilometres around the territory as built over 40 to 100 years ago, 57 km were built before World War II, supporting various reservoirs/groups of reservoirs. They were constructed as waterways that cut into the natural hillsides before World War II. Therefore, the majority of these catchwaters are linked to man-made slopes. Catchwaters are either open channels or enclosed tunnels, which can suddenly fill with rainwater during flash floods. It is advised that people should not enter catchwaters as quickly rising water levels can be dangerous.

In addition, to prevent contamination of raw water in gathering grounds, the Waterworks Ordinance, Cap. 102, stipulates that no person shall enter, bath or wash in water forming part of "waterworks". This includes the gathering ground, which is defined in the legislation as "any surface of land in or by which rain or other water is collected and from which water is, or is intended to be, drawn for the purposes of a supply". Interestingly, the catchment area referred to in the legislation includes not only the geographical natural catchment area, but also the man-made development of the whole water gathering system, i.e. the engineering design plus the whole system of catchwater in the natural catchment area.

Rome was not built in a day. The development of such large water gathering systems in Hong Kong has taken over a century, and continues to serve and nourish the city today. From the first days of the Water and Drainage Department of the former Public Works Department, to the present-day WSD, these government departments have effectively maintained uninterrupted operation of the entire water supply system for over a century, providing an adequate water supply to the general public today - a formidable task indeed.

- Pok Fu Lam Reservoir was inaugurated in 1863. As the capacity of the reservoir was insufficient, in-situ expansion works commenced in 1866 and were completed in 1871.